Can You Stop Investing When You Hit Your Retirement Number?

“The rearview mirror is always clearer than the windshield.” — Warren Buffett

Remember those ING ads where people were carrying around big orange random numbers?

Those numbers represented the amount that they needed to have in assets to have a safe and secure retirement.

The ads were trying to create awareness that there’s a magical, mystical “number” that supposedly guarantees that you won’t have to eat cat food or dive in dumpsters when you stop working.

I was recently at a FinCon meetup with PT, and he asked me a thought-provoking question.

He was looking at the sum in his retirement accounts. He took that number, assumed a certain rate of return in the market between now and when he reached age 59 ½, and the result was his “number.”

“Does this mean I can stop contributing to retirement accounts?” he asked me.

Before we can start to answer that question, let’s dig a little more deeply into the issue.

Retirement Accounts: Why 59 ½ is a “Magic” Number

Many years ago, the U.S. government decided that it would be in the best interests of folks like you and me if we started saving for our own retirement. Social Security was originally meant to effectively match the average life expectancy of an American.

So you’d work until age 65, retire, and, on average, drop dead. No need to pay benefits. It’s also not meant to be your primary source of covering your living expenses. The legal term for Social Security is OASDI: Old Age Survivors and Disability Insurance. It’s insurance. If it was meant to be income, then they would have called it such.

But, we Americans came to rely on Social Security as more than just a security blanket for when we got older, and we, on average, started outliving that pesky age 65 milestone. The amount spent on Social Security started catching up with the amount put into the lockbox, which is a different story for a different day.

Thus, the government decided to give us an incentive to sock away money for retirement. We needed incentives, after all. We all have a part of our brains derived from the limbic systems that we share with monkeys, which I call Monkey Brain.

Monkey Brain wants pleasure, and he wants it NOW. He doesn’t care that, at some point in the future, we’re going to have to deal with all of the negative repercussions of our decisions. That Future You is a stranger, and, therefore, we don’t value Future You’s pleasure nearly as much as we value our own pleasure.

This is called hyperbolic discounting, and it’s because of hyperbolic discounting that we need incentives to save for our retirement. If it were up to Monkey Brain, we’d spend all (and then some) of our money now on toys, gadgets, and sparkly shoes, and through some act of magic involving rainbows, unicorns, and a large stack of bacon, we’d wind up in retirement with everything hunky-dory.

Thus, we have to create incentives to set aside money for our retirement, or we’ll never do it. We’ll carpe diem until there are no diems left to carpe. That’s why the government created a retirement plan structure that gives us tax incentives to set aside money for later. I’m sure if I look in the Congressional Record, I’ll find the term “Monkey Brain” somewhere.

There are two main types of tax-advantaged retirement accounts that I’ll briefly describe: employer-based and individual.

- Employer-based: these retirement accounts are ones where your employer either funds or matches what you put into the retirement account. The most common ones are 401ks, 403bs, 457s, and TSPs.

- Individual: these retirement accounts are ones where you’re responsible for funding the account. This is your standard IRA.

There are also, in most plans, two choices for tax treatment of the funds down the road:

- Traditional: In a traditional account, you defer taxes until you withdraw the funds from the account. You usually get a tax incentive now – in the form of a deduction from your current taxes. Then, later, you’ll pay ordinary income taxes on what you withdraw, no matter how much it has or hasn’t grown.

- Roth: In a Roth account, you pay taxes now and contribute to your Roth accounts with after-tax dollars. In exchange, you get to withdraw the money tax-free when you retire. There are restrictions on Roth eligibility for some accounts based on your adjusted gross income.

Related: Should You Participate in Your Employee’s Stock Purchase Plan

The government gives you a carrot to create an incentive for you to contribute to these accounts, but it also has a stick to beat you with to keep you from withdrawing too early. That’s the early withdrawal penalty, and it’s usually 10% of what you withdraw. In general, with some employer-sponsored plans, like the 401k and TSP, this is age 55, and with most IRAs, it’s age 59 ½.

Withdraw before the magic age, save for some certain hardship conditions, and you get whacked with a 10% penalty along with having to pay the applicable income taxes. Wait until after the magic age, and you’re golden (though there are also penalties for not taking enough out of traditional retirement accounts once you reach age 70 ½).

That’s why PT mentioned 59 ½ as the magic age.

But, should he stop contributing since he’s projected to hit his “number” by taking the ultimate couch-potato approach and doing nothing more than letting the market do its magic?

What are your options if you’ve hit the “retirement number” but you’re not retirement age?

There’s an inherent problem with hitting the number but not yet being at the age to take advantage of the number.

You still have to support yourself between now and the time you reach that number.

Oh, for time travel.

There are three options for what to do with your investment money, each with its pros and cons.

- Continue to squirrel away for the future in your retirement accounts. The strongest case for this one is if you have an employer-matching contribution. There’s nothing in the world like free money, and it’s a guaranteed return on your investment right off the bat.Pros:

- You continue to decrease the probability that you’ll run out of money during retirement. While you can’t ever get to a 0% chance of running out of money in retirement, you can continue to make that number approach zero as you contribute more.

- You can increase your standard of living in retirement. If you’ve always wanted to take that cruise around the world or to buy a beach house in retirement, then continuing to sock away money will give you the financial flexibility and freedom to do just that.

Cons:

- You still can’t get to that money until you reach the retirement age specified in the retirement plan. Depending on just how much money you make, you may be making tradeoffs between now and the future – if you’re making an either/or decision on your investment capital.

- You may never be able to spend all of that money. That might be fine if you want to leave a large inheritance for benefactors, but studies show that as we age, our spending decreases. Very few 110-year-olds are traveling much, no matter how much they want to do it. It’s just not physically possible. They also don’t eat much either. Both their needs as well as their physical ability to do things is quite limited; therefore, their income requirements are much less than their younger counterparts.

- Sock away money in taxable accounts. Invest in standard brokerage accounts, investment real estate, your own business, whatever. There are no tax benefits to the investments; therefore, there are no tax penalties to withdrawing the money whenever you want either.Pros

- You improve your chances of retiring earlier. If you have enough money in taxable investments set aside to meet your living requirements until you reach the age that you can tap into your retirement accounts without paying penalties, then you get to retire. Whoo whee!

- You’ll want investments in taxable accounts for tax optimization when you retire. The how and why of this topic is beyond the scope of this article, but there are tax reasons for having money allocated to taxable and tax-advantaged accounts when you’re retired.

Cons

- You can never be sure that you have enough to retire, so you’re taking a smallish risk that your retirement accounts will be of a sufficient size by the time you reach your retirement age. This isn’t as big of a risk as not investing at all, as all you’re doing is paying taxes now when you could be using that money to invest and defer taxes, but it does create some risk.

- You may be encouraged to take inappropriately risky investments. Again, this won’t happen to a large degree, but our limbic systems will create a separate mental bucket for these investments and we may wind up convincing ourselves to swing for the fences with this money investing in pork snout futures or your brother’s “can’t miss” deli in southwestern Antarctica.

- Increase lifestyle now. You’ve got the money, so live a little!Pros

- You’ve been working hard all of your life, so now you get to enjoy some of the benefits. Have you been wearing the same taped-up shoes for the past fourteen years? Time to get some new threads! Welcome to the world of HDTV! No more Ramen!

- Present fun means more to Monkey Brain than future fun. Since you’re not going to have to scrimp and save and scrimp and save, Monkey Brain will get off of your back about never being able to have any pleasure. The lack of rattling from his cage in the middle of the night will mean you get to sleep more soundly.

Cons

- The increase in lifestyle means that you’ll have to increase your retirement number. When we increase our lifestyle, we undergo a transformation called hedonic adaptation. Soon, steak tastes like chicken and we’re left wanting lobster and caviar. When we retire, we’re surely not going to want to have to dial down our lifestyles. Therefore, we need more money in the retirement accounts to account for this increase.

- We can never get back the opportunity to invest. Compounding is one of the most powerful factors in the universe. The older you get, the more you have to save to get to the same target point. If we wind up needing more money later, we’ll rue the day that we decided to go buy that 183″ flat screen television.

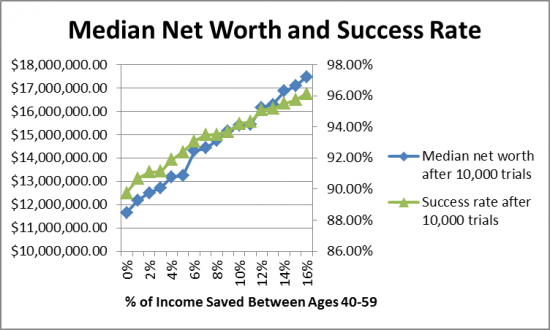

I also wanted to look at what happened to people who have contributed enough to be on pace for appropriate retirement savings if they quit saving, or if they kept saving. So, I created a Monte Carlo simulation that evaluated 10,000 potential futures.

Since we know that it’s impossible to create the Unified Formula of Financial Planning to account for stock and bond market returns and inflation, I used Monte Carlo simulations, which create random futures based on historical ranges.

In this case, I used the annual stock market returns from 1871 to 2012, ranging from -44.2% to +56.79% with a median of 10.5%, corporate bond returns since 1919, ranging from 2.54% to 15.18% with a median of 5.2%, and inflation rates since 1914, ranging from -10.5% to 18% with a median of 2.8%.

I assumed that PT was 40 and that he would retire at age 60 and, at retirement, he and Mrs. PT would draw enough in Social Security to pay for half of their expenses at the time.

I assumed that their monthly expenses in today’s dollars were $4,549.94, making their target number $2.5 million. I also assumed that they were invested 60% in equities and 40% in bonds and would remain so throughout life (not necessarily the best suggestion, mind you, but I did it for ease of calculations).

If we assume a compound average growth rate of 7.5%, then in order to have enough set aside to be able to stop investing and reach the $2.5 million target number by age 60, the Family PT would need to have $588,532.87 set aside by age 40, so I assumed that they had that much.

I assumed that the Family PT kept working until age 60 and that they earned enough to contribute 0-16% of their income per year, and income and expenses rose with inflation. Once they reached age 60, they quit and lived off of their investments until age 67, when Social Security kicked in.

How did they do?

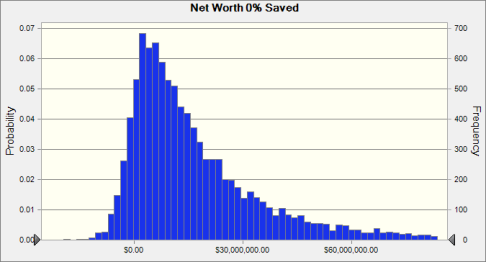

The reason I chose the median value is that high results skew the overall average. I wanted to see where the Family PT would most likely be, and median numbers show the case where 50% of the results were above that number and 50% of the results were below that number. Let’s look at the net worth distribution for saving 0%.

As you can see, there are some great outcomes, but the results are bunched between $0 and $8 million.

When I run these models for clients, I recommend that if there is a 90% success rate or higher with the plan, they can run with it, and change the plan later on if results aren’t meeting their expectations.

In PT’s case, the right answer is probably a mix of all three of the options above. He can increase his lifestyle a little, bump up the retirement savings to account for the increased lifestyle expectations, and save some in taxable investments to try to reduce the magical retirement age.

What about you? Have you been asking “when can I stop saving for retirement?” Do you have your number figured out? Are you starting taxable investing or are you piling up money in retirement accounts?

![The Best Retirement Calculators for 2023 [Compare These 15 Tools]](png/screen-shot-2022-03-24-at-11.30.24-pm.png)

HullFinancial fastsquatch Interesting – you were linked off Simple Dollar so it’s my first time here, I followed those links and they’re very well done. Agreed on all points (which is easy since facts are easy to agree on 😉 ), and I see what you mean – sticking to the question with retirement pegged at 59 1/2 means the reasoning is spot on. I suppose my failure to imagine someone hitting their number and not retiring reveals something about my own mindset, but if I look deeper I realize that even post-early-“retirement” (assuming I achieve it) there’s a strong likelihood there will be enough taxable income that making retirement contributions (or your other options outlined) may make sense. Good stuff.

fastsquatch Hey, Fastquatch (love the name!) – you’re right in bringing up the SEPP/72(t) possibility. Had PT asked about funding early retirement, I would have included it (as seen here: http://www.hullfinancialplanning.com/how-do-you-bridge-the-gap-between-early-retirement-and-age-59-12/). As it was, he asked about 59 1/2, rendering SEPP moot, since you have no periodic payment requirements until RMDs at 70 1/2.

You do raise a good point about confidence levels in a simulation (which is subject to its own input errors). A 90% chance of success doesn’t mean that you’re doomed to eat cat food 10% of the time. It simply means that you would need to make adjustments along the way and reduce your expenditures so that you don’t run out of cash before you run out of heartbeats. I think this is one area where the financial planning community falls way short in communication, as presenting probabilities of plan success sometimes implies, unintentionally, this dramatic cliff when the plan doesn’t work. See http://www.hullfinancialplanning.com/how-bad-is-bad-the-magnitude-of-failure-in-retirement-planning-scenarios/ for more.

Hi there – not to complicate an already complicated topic too much (though I love a good Monte Carlo simulation), but I think this article ignores something huge – there are exceptions to the tax on withdrawals prior to 59 1/2, you may take “substantially equal periodic payments” without penalty.

They must be scaled to your life expectancy, but you may even alter them later if needed (though there are restrictions on alterations – you can’t alter them within the first 5 years for instance).

That renders this analysis semi-moot – as your subject should definitely continue to put money in tax-deferred accounts, using a Roth / Traditional mix to balance future tax risk if desired, then if early retirement is desired start actuarially correct substantially equal payments et voila?

The larger point about increasing success or standard of living by continuing to save is obviously valid and important though. 90% confidence level is still a non-zero chance of cat food after all.

But with regard to early withdrawals without penalty, I might be missing something – would love to be corrected if so.

Citation: http://www.irs.gov/Retirement-Plans/Retirement-Plans-FAQs-regarding-Substantially-Equal-Periodic-Payments#2

@Jeff Good catch! They started out at age 40 with $65k in combined annual income.

What were the yearly contributions between 40-59? You state 0% to 16% of income but I don’t think you state the amount.

Jason nice piece and a great analysis. Your six bullet point questions near the end are of course the essence of what we both do as financial planners. Certainly the right answer or combination of answers will depend and vary case by case. However I uniformly caution pre-retirees that retirement age is just another blip on way, your investment horizon should be your lifetime(s) at least.